Learning to Detect Multi-Modal Grasps for Dexterous Grasping in Dense Clutter

Figure 1: Our system selecting an optimal grasp pose and grasp type for picking an object from clutter, then executing the grasp to sequentially clear the table.

Grasping is one of the most important open problems in robotics — it is the most essential skill for pick-and-place tasks and a prerequisite for many other manipulation tasks, such as tool use. If robots are to one day perform the complex manipulation tasks humans are capable of in varying home and workplace environments, they must first master grasping. Humans use multiple types of grasps, depending on the object, the task, and the scene. A human may perform a large-diameter power grasp to stably grasp the handle of a heavy jug, but a precision sphere grasp to lift a golf ball off the ground. If the clutter around an object precludes one particular grasp type, humans simply switch to another. It is therefore natural that the ability to use multiple grasp modalities would substantially improve robots’ ability to grasp a wide range of objects, especially in dense clutter.

We propose a data-driven grasp detection framework that, given partial depth data and a grasp pose, jointly predicts the grasp success probabilities of several types of grasps. We train a deep neural network to perform this joint classification using a dataset containing grasp candidates generated from real point clouds and grasp labels generated in simulation. Given a point cloud — captured from an arbitrary number of depth sensors in arbitrary poses — along with a grasp pose, our network outputs a probability for each available grasp modality. These values reflect the probability that the corresponding type of grasp would succeed at the given pose. Unlike state-of-the-art antipodal grasp detectors and many multi-finger grasp detectors, we model grasp type explicitly. Our system does not assume the gripper is fully actuated and can control finger placement. Furthermore, we evaluate our system on a real robot in dense clutter.

Multi-Modal Grasp Pose Detection

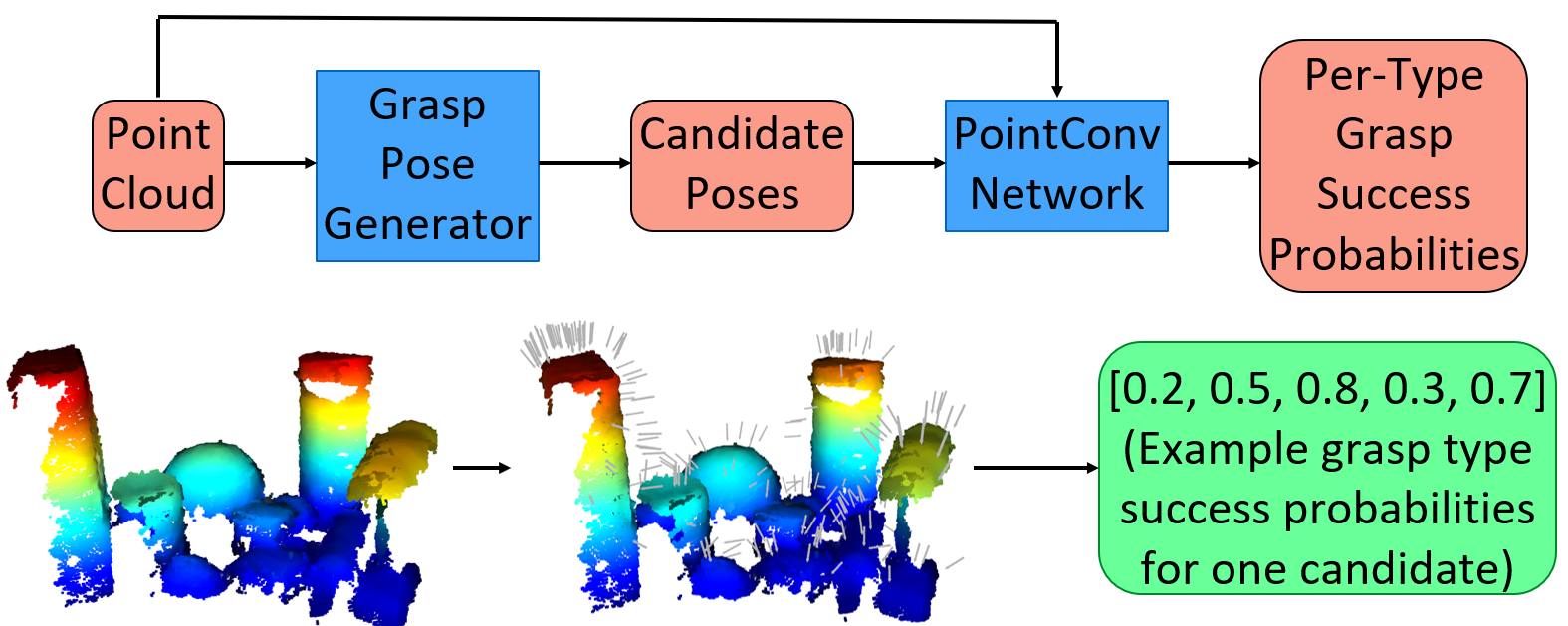

Our system follows the two-stage proposal-evaluation paradigm. In the first stage, an off-the-shelf grasp pose generation algorithm proposes a large set of 6-DoF poses that could lead to a successful grasp. Each of these candidates is evaluated in the second stage. While existing works predict the probability that a grasp would succeed given a pose, our system predicts the probabilities that each grasp type would succeed given a pose. This evaluator is implemented as a deep neural network that encodes point clouds directly using PointConv layers, and outputs five independent probabilities.

Figure 2: A diagram of our system. Given a point cloud, which can be a concatenated cloud from several sensors and can contain multiple, unsegmented objects, the grasp pose generator proposes a set of grasp candidates. Our multi-modal grasp quality neural network then predicts the probabilities that grasps of each type would succeed at each proposed pose.

Multi-Modal Grasp Quality Network

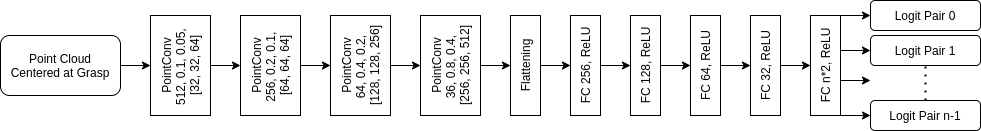

Our grasp evaluation neural network takes as input a single point cloud, centered at a candidate grasp pose and cropped to contain only points the gripper would likely encounter. This cloud is first encoded using a series of PointConv layers. The output from the final encoding layer is fed through a series of fully connected layers with ReLU activations. The final fully connected layer outputs a logit pair for each of the n grasp types the gripper is capable of. We output two logits per grasp type in order to train the network to perform binary classification on each grasp type and predict whether a grasp of each type would succeed or fail. These logit pairs are passed through n independent softmax functions. The n resulting probabilities corresponding to positive labels can be interpreted as the probabilities that a grasp at the given pose of the corresponding grasp type would succeed.

Figure 3: Network architecture of our Multi-Modal Grasp Quality Network. Given a point cloud centered at a grasp pose, the network predicts the probabilities that a grasp of each of the possible grasp types would succeed at that pose.

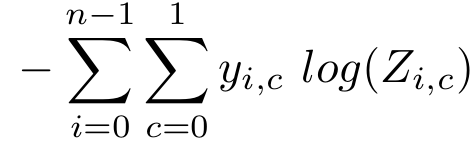

We train this network to jointly perform n binary classifications using a summed cross entropy loss function. Joint binary classification is useful in cases where multiple entangled predictions are made from a single input source. By training a single network to perform joint binary classification, our system learns an embedding that efficiently encodes the information required to determine whether each grasp type succeeds given a cloud and grasp pose. Though joint binary classification has been proposed to solve problems such as emotion detection, ours is the first robotics application we are aware of that uses it.

Figure 4: Our summed cross entropy loss function, where the cross entropy between each grasp type label and prediction is summed.

Here, y is 1 if c is the correct label for a given exemplar’s grasp type i, and Z is the output of the neural network after being passed through the softmax functions.

Grasp Quality Dataset

In order to train our multi-modal grasp quality network, a dataset of labeled grasp exemplars is required. The BigBIRD dataset contains a set of real partial point clouds captured from 600 viewpoints on a set of common household products and a complete mesh for each object. BigBIRD is a popular dataset for training grasp detection systems since no simulation-to-real transfer is required with real point clouds. Our grasp dataset is generated from 20 BigBIRD objects and 12,000 point clouds. Given a real point cloud, we propose a set of candidate grasp poses, then generate a set of n binary labels per pose by attempting a grasp of each type at each pose in simulation.

Though our framework is compatible with any robot gripper and its n, grasp types, we train and evaluate our system with the Robotiq 3-Finger Adaptive Gripper, a 4-DoF, 11-jointed underactuated gripper. This gripper is designed specifically to perform different types of grasps, which are shown in Figure 5. The gripper’s grasp type is parameterized by grip type and operating mode. Precision grips are achieved by grasping objects with the distal links, while power grips require the palm to be close to a grasped object’s surface. A single motor controls the operating mode by setting two fingers to be parallel in basic mode, spread apart in wide mode, and brought together in precision mode, which mimics a parallel-jaw gripper.

Figure 5: A Robotiq 3-Finger Adaptive Gripper’s five main grasp types.

Our dataset’s labels are generated in the Drake simulation environment to accurately simulate the Robotiq 3-Finger Adaptive Gripper and its grasp types. Each grasp type is executed on simulated models of the BigBIRD objects at each of the 36,000 proposed grasp poses to generate n binary success labels per candidate pose.

Figure 6: Our simulation of the Robotiq gripper executing all five grasp types on a cylinder and a box.

Learning a Multi-Modal Grasp Quality Function

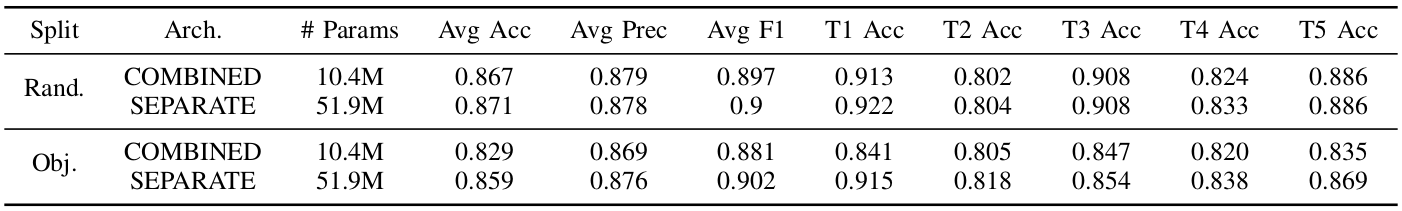

We first evaluate our system by testing its performance on several held-out datasets. In the first scenario, the test set is comprised of 15% of the grasp candidates in our dataset, selected at random, while the remaining 85% are used to train the network. The second, more difficult scenario tests how well the system generalizes to unseen objects. Here, the test set contains all grasp candidates from 15% of the objects in the dataset, while the grasps on the remaining objects are used to train the network. In each scenario, we compare our architecture that outputs five predictions per pose from a shared embedding (COMBINED) to a similar architecture that uses an ensemble of n individual deep networks to predict grasp success for each grasp type (SEPARATE). These individual networks are a naive approach that uses n times as many parameters as the combined network, but provide an upper bound to compare our system against. Figure 7 shows the test-set classification accuracies of our system and the baseline trained and tested using the two dataset divisions. These results are each averaged over three random seeds used to divide the dataset.

Though test-set accuracy demonstrates how well the system learns, when executed on a real robot, selecting false positives can cause a low grasp success rate. Since the system chooses to execute the one grasp with the highest predicted success probability, the grasp may fail if an incorrectly classified false positive is selected. False negatives, however, are not as detrimental to the grasp success rate since the system will choose only one of the many grasps expected to be successful. It is, therefore, also important to verify the system’s precision and F1 score.

Figure 7: Simulation results.

As COMBINED is trained to predict success for all grasp types, all statistics are reported at the epoch at which average accuracy across all grasp types is maximum; the individual grasp type accuracies are not necessarily maximum at this epoch. For SEPARATE, since each network is trained with only one grasp type, each accuracy, precision, and F1 score are reported at the epoch at which that grasp type’s accuracy is maximum. The reported average accuracy is the average of these maximum accuracies. Despite this, when learning these binary classifiers jointly from a shared embedding, the average classification accuracy decreases by only 0.4% when test objects have been seen and 3.0% when the training and test object sets are exclusive. Furthermore, our system achieves a higher precision in the case where test candidates are selected at random. These experiments show that jointly training individual classifiers from a shared PointConv embedding enables our system to more efficiently classify grasp poses with a negligible loss in performance compared to a similar set of networks with five times as many parameters.

Clearing Clutter with Multiple Grasp Types

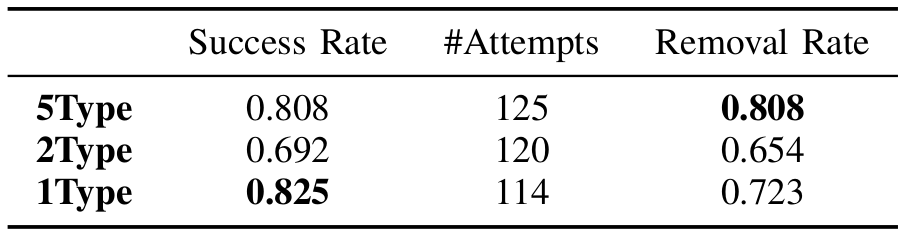

We perform real-robot experiments to measure how much multi-modal grasps help to clear objects of varying sizes from a cluttered table. To examine the benefits of multiple grasp types when grasping in dense clutter, we compare our system to two baseline ablations representative of related work whose deep networks have not been trained to assess all five grasp types. The first, 1Type, predicts only the probability that a pincher grasp would succeed, and is representative of systems designed for parallel-jaw grippers. The second, 2Type, predicts whether two grasp types, basic power and basic precision, would succeed, similar to other multi-finger grasp detection frameworks. Our system, 5Type, models all five Robotiq grasp types.

In each of our experimental trials, a random selection of ten small and medium objects is placed in a box, shaken, and dumped into a cluttered pile on a table; three random large items are placed around the pile after dumping the box to ensure they remain upright. This scenario is designed to challenge the system, as it may depend on all five grasp types to clear the table. The objects used in these experiments, an augmented segment of the YCB dataset containing six large, 17 medium, and six small objects, did not appear in the training set and can be seen in Figure 8.

Figure 8: Objects used in our robot experiments.

We capture two point clouds from fixed locations, then remove all points within a threshold of the known table plane. After generating a set of 400 candidate poses, candidates that would cause collisions, contain an insufficient number of points in the graspable region between the fingers, or are unreachable are filtered. The remaining candidates are evaluated with the multi-modal grasp quality network; the grasp pose and type with the highest predicted probability of success is executed.

The system attempts to grasp objects until either:

- the same type of failure on the same object with the same grasp type fails three times in a row,

- the system fails to generate reachable grasps in three consecutive attempts,

- all objects are removed from the table.

If the system fails to find a feasible grasp or the motion planner fails to find paths to the top 25 grasps, we repeat the candidate generation process up to two more times, each time proposing twice as many candidates. A grasp is successful if one or more objects are lifted from the scene and moved towards a box, and do not fall from the gripper until the fingers are opened. If an object leaves the workspace during an unsuccessful grasp or during a grasp on a different object, it is placed back in the scene near where it left, abutting as many other objects as possible. If an unforeseen collision occurs during a grasp or placement execution, the disturbed objects are reset and the attempt is not counted. Each system is presented with the same objects as the other systems in each of the ten trials, but in a different random configuration. We report both the grasp success rate (number of successful grasps divided by number of attempted grasps) with number of attempts and overall object removal rate (number of objects removed from table at the end of a trial divided by initial number of objects). The results of this experiment is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9: Robot results.

Our system with access to all five grasp types, 5Type, outperforms the ablations of our system, 2Type and 1Type, when grasping items from cluttered scenes surrounded by large objects. 5Type achieved the highest object removal rate by successfully clearing nearly all scenes. In some trials, though the grasp generation algorithm proposed grasps on the small Lego or duck, the motion planner failed to find a path to these grasps. A common failure mode of the system, which is a common failure mode in other grasp detection systems, was that it attempted to grasp multiple objects at once. The 5Type system suffers from this issue more than the baselines because it has access to wide-type grasps that spread the fingers out and are more likely to contact multiple cluttered objects. Therefore, the grasp success rate of the 5Type system was lower than that of the 1Type system. The issue could be alleviated with an off-the-shelf depth image segmentation algorithm and an additional filtering step in the grasp generation algorithm. Other failure modes of our system include false positives and objects moving as the fingers close. The system also struggled with the heavy shampoo bottle in two of the five trials it appeared in. Because our grasp evaluation network makes predictions based only on local geometry, it incorrectly predicted that unstable grasps would succeed. Since our system has no notion of grasp history, it became stuck in a local minima and unsuccessfully attempted similar grasps three times in a row, ending the trials. However, in three of the trials, it correctly used power grasps to stably lift the heavy bottle.

Since 2Type is incapable of performing pincher grasps, it often fails to find feasible grasp candidates on small objects that fit between the gripper’s spread fingers. The system encountered difficulty with the rice box in one trial and the pear in another, objects that the 5Type system never failed to grasp. However, because this ablation did not have access to the weak but precise pincher grasps, it was able to successfully grasp the heavy shampoo bottle in three of the five trials it appeared in. The 1Type system outperformed the 2Type system in these experiments because pincher grasps succeeded on the small or medium objects that made up the majority of our object set. Even most of the large objects were light enough that they could be lifted with a pincher grasp. 1Type attempted to grasp multiple objects at once less frequently because the fingers are not spread apart during a pincher grasp. The 1Type system successively failed to lift the heavy shampoo bottle by its cap three times in three different trials, ending the trials prematurely and decreasing the object removal rate.

Our 5Type system was able to choose applicable grasp types for the situation to clear each scene more completely. It used a wide power grasp to stably grasp the top of the drill, and another to perform a spherical grasp on the soccer ball, one of the largest medium-sized objects. It used basic power grasps when faced with the heavy shampoo. The 2Type system also selected basic power grasps for these objects. Overall, our 5Type system executed three wide power, 33 wide precision, six basic power, 38 basic precision, and 45 pincher grasps. Collision-free power grasps were rarely generated on the small and medium-sized objects because they lie close to the tabletop. As the large objects were often partially occluded by the adjacent clutter pile, their larger graspable areas were hidden. Though our 5Type system chose to use fingertip grasps in the many applicable scenarios, it used power grasps to lift the heavy objects the 1Type system often could not.

Watch the video below to see a trial with the 5Type and 1Type systems.

Conclusion

The simulation experiments show that our system is able to efficiently learn to jointly evaluate multiple grasp types for a given grasp candidate. Our real-world experiments show that this architecture enables a robot equipped with a multi-finger gripper to more successfully clear a scene of cluttered objects of various sizes from a tabletop than systems that use fewer grasp types.

The full paper is available here, and a video presentation of this work is available here: